By Vanessa Salvia

The introduction of ICF to the Brigham Young University Hawaii campus represents a significant milestone for the industry for a number of reasons. First, it represents a major step forward in sustainability for the buildings on the island of Oahu. Due to the environmental conditions along the windward side of Oahu and its maritime environment, other cementitious building materials would be vulnerable to the moist, salty prevailing wind. But using an ICF product encapsulates the concrete within the ICF foam form. Another reason is the extremely high cost of energy. With electrical rates at nearly three times that of the continental U.S., it makes sense to consider a building system that will reduce energy costs. It is also likely to be the largest ICF project undertaken anywhere in the world. We can’t confirm that, but if there’s a bigger project out there we hope to hear about it.

BYU Hawaii is a private university and sister school to BYU in Provo, Utah, that was founded by Brigham Young in 1875, and is sponsored by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. BYU Hawaii’s original construction began in 1955 and now, a large percentage of it is being replaced and rebuilt with ICF. Much of the masonry work on the Hawaii campus is being done by IMS Masonry, a masonry trade partner to both Jacobsen and Okland construction companies, based in Utah. IMS is one of the largest masonry contractors in the Western United States and they include among their projects some of the largest ICF projects in the country. IMS is also based in Utah, and they have previously done a lot of work for the Church and recently finished the ICF installation for the Church’s first ICF temple, the Moses Lake Washington Temple.

Buildings Subject to Flooding

The BYU Hawaii project is raising and replacing approximately 20 buildings on campus, most of which are housing-related projects that have been subject to flooding during extensive periods of rain. The main classroom building, the McKay Classroom Building, has reached its life cycle and a replacement building is in the design process. This will consist of six buildings, and it is currently projected to be built out of ICF. They are in hopes of extending the life cycle from 50+ years to well over 100 years by using ICF. As of 2020, builders had completed 32 townhome buildings with more ongoing.

Kirk Tyler was a project manager for the project in Hawaii but has since left the island and returned to Utah. Although his career is now with large Utah-based general contractor BHI, he is still involved in the BYU project. He was instrumental in choosing ICFs for this project. Tyler was a builder by trade and had experience with ICF in the Park City, Utah, area years prior. After doing his due diligence to research the project, he was certain that no other building material would match the durability and energy savings of ICF.

When asked about what was driving the decision to use another building material, Tyler responded that, “the windward side of Oahu is one of the most corrosive environments anywhere, because the prevailing winds constantly blow moist salty air across the landscape. Building with ICFs here just made all the sense in the world.”

TVA Project

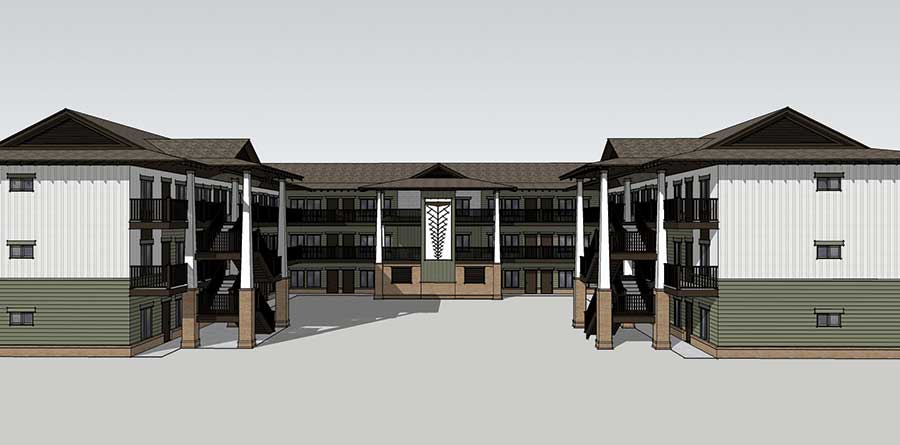

The married student housing project consists of a three-story building using 6-inch Fox Blocks blocks. When Tyler and I first spoke a year ago, the project was four years into a roughly 10-year project timeline.

There are two main drivers for these projects: One, the campus is turning away students because they simply don’t have room, and two, FEMA is strongly enforcing its floodplain, threatening the state of Hawaii that they will pull out if the state doesn’t start enforcing it, explains Tyler. This being said, the state building department established new enforcement policies on building projects, one of which is that if a building that is below the floodplain and is in need of repair, in a five-year period, the cost of the renewal cannot exceed 50% of the original appraised depreciated value. This has caused BYU Hawaii to have to raze the old buildings and replace them at the new building flood elevation. In addition to this requirement, FEMA has elevated the floodplain since BYU Hawaii started this renovation.

“There are new buildings here and replacement buildings,” says Tyler. “The housing area is probably the biggest portion of the projects. Most of the existing buildings are in need of repair, to the point where it exceeds the above said amount of money to be invested into the repair to meet the state building department requirements and the new floodplain.”

In 2020, the school completed the Temple View Apartments (TVA) with three buildings in different layouts of 28 units each. This is just the first phase of four that will help in densifying the building footprint being built. The campus is also completing three four-story dormitories. As of September 2020, the project had completed 32 townhomes with more planned. Altogether, there are 35 townhomes in 13 different buildings of about 2,000 square feet each.

The first phase, the TVA buildings for married students, have layouts of one or two bedrooms. The second phase will include a mix of one and two bedrooms in addition to six apartments that are three bedrooms. There will also be a fourth phase with more buildings identical to the first phase. The first-phase plan was to give the campus flex room for the need of moving families out of the buildings that are being razed and replaced. The project also includes five U-shaped buildings that will have a courtyard in the middle for a playground and common area. Each of the buildings is three stories high, contains 52 apartments, and is equipped with elevators to accommodate ease of access.

Hale Project

Groundbreaking for buildings known as Hales 11-13 commenced on November 5, 2021. These Hales are apartment-style buildings similar to Hales 4, 5, 6, 7, and 10. Plans for the new Hales include apartments for four to six students within each unit. Each floor will have approximately 14 units, and each Hale will have four floors. The new project will add housing for 900 to 1,000 single students.

The four-story dormitory buildings are two L-shaped wings that are placed together in an oval or rectangular shape with connecting walkways under one roof system. Kirk says the ICF’s six-inch concrete core works well because the buildings stack vertically and helps in keeping the STC’s low between dorm rooms.

Conclusion

It’s clear that ICF is the best choice for new buildings of all types, but especially in a campus setting like this, and also for an island setting like Hawaii. These new buildings will elevate the student experience on this campus as well as provide for safe, durable buildings for students to live in for years to come.

Vanessa Salvia

Editorial Director