Cement-EPS Blends Are Eco-Friendly

The green building movement, already a huge factor in the commercial sector, is likely to transform residential construction as well. One expert claims it will transform the industry the same way electric lights and air conditioning did last century.

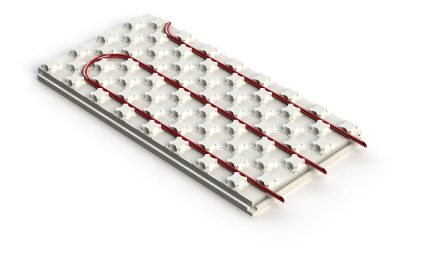

Insulating concrete forms (ICFs) are well-positioned to take advantage of this trend; they’re durable, energy-efficient, and widely available. Among the various types of ICFs on the market, perhaps the most environmentally friendly are the so-called composite ICFs, blocks made from a mix of expanded polystyrene (EPS) and Portland cement.

“We are greener than the typical ICF,” claims Brandon Dardanis, a principal at Tech Block International. “We use more recycled polystyrene, and have a better R-value, and a better dynamic R-value as well.”

Recycled Content

“Composite ICFs use a huge amount of recycled EPS that is usually destined for the landfill,” confirms Orb Sumrall, vice president of Amazon Forms. “Consider how many thousands of gallons of fuel, energy and labor are saved annually by no longer running landfill equipment. Consider also that EPS is a non-biodegradable product, which means we’re saving space at landfills as well.”

Kark Holik, president of Rastra Corp. has hard numbers to back up this assertion. Holik invented the composite ICF more than 35 years ago, and is by far the largest manufacturer of this type of block.

“We use 100% post-industrial, post-consumer waste, in all of our blocks,” says Holik, noting that traditional ICFs are limited to 10% non-virgin materials. The foam is provided by local recycling organizations; their Ohio facility uses material collected by Solid Waste Authority of Columbus Ohio (SWACO).

“The most important thing is we take materials out of landfills that otherwise might stay there for 100 years or more,” he says. “We’ve done studies on a landfill operated by SWACO. By keeping all of the EPS out of the landfill, they save $600,000-$700,000 a year in direct savings, plus 4-6% savings in landfill space.”

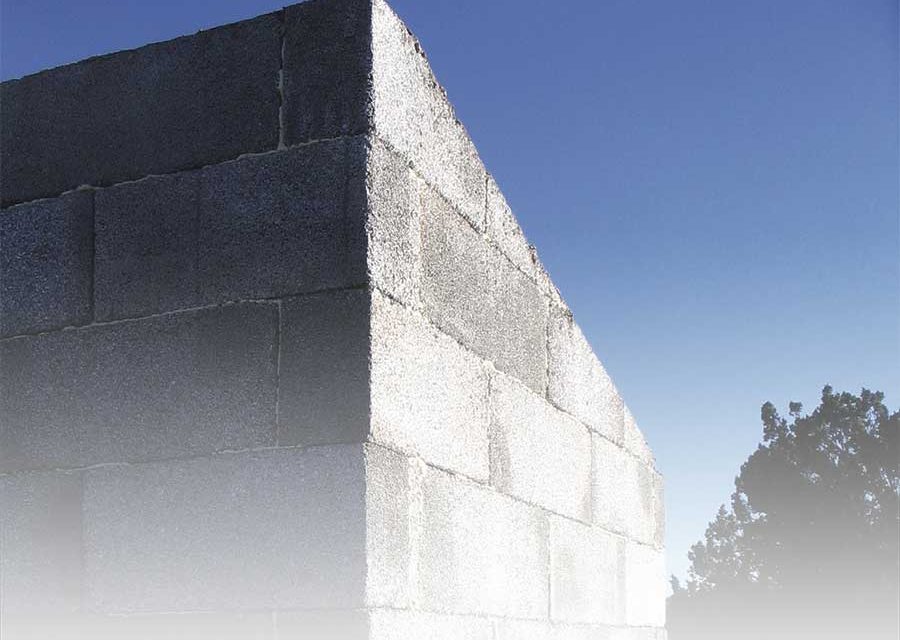

Increased Durability

“What we do is grind up the foam and coat it with cement, which changes the properties completely,” Holik says. “It becomes completely non-burnable, and still has a very high insulation value.”

Earlier this year, Amazon’s Grid-wall was tested at Southwest Research in San Antonio, Texas. No coatings of any type were placed on the block. After two and a half hours of burning, the sensor on the non-fire side rose only two degrees Farenheit.

The walls are similarly impervious to mold, termites, and other pests, Sumrall notes that this type of block will provide termite resistance without any type of pesticide or special treatment that may leach into the soil.

Less Material

Composite ICFs will accept drywall mud, Portland stuccos, and acrylic polymers (sometimes called textured acrylic finishes) applied directly to the block. Other wall types, including traditional ICFs, must be coated with 5/8” drywall to meet fire code. Composite blocks do not require drywall, although most builders install it anyway.

Holik notes that because composite ICFs are heavy—about 10 pounds a sq. ft.—and are ten times as dense as pure EPS foam, they require less bracing during construction. “We’re all trying to save trees,” says Sumrall. “Reduced bracing and seam reinforcement means using less wood.”

There are other savings as well, such as using less petroleum to make virgin EPS beads, and less cement, which is a notoriously energy-intense process.

“Most composites will use 30% less concrete than a comparable wall made from all-foam ICFs,” says Dardanis. “Cement production uses an extreme amount of energy and produces a lot of carbon. By decreasing the amount of cement, we can decrease carbon emission by a significant amount.”

Other considerations

Dardanis also notes that reducing the concrete in the wall translates to better insulating properties. “If we use two-thirds the concrete, then there’s one-third more insulation in the wall,” he says. When completed, the wall performs even better; its substantial thermal mass dampens sudden temperature swings.

Builders like the fact that they can be cut and shaped with standard carpenters tools.

Drawbacks

Dardanis notes that the blocks do have drawbacks. “The flat wall design [of regular ICFs] has advantages for tall walls, and it’s what the engineers are familiar with. However, composite ICFs are great for commercial work.”

But in the residential sector, composites may be the best option for minimizing the environmental impact of construction.

“If LEED certification is important to the developer or owner, they will get extra points for using composite blocks,” says Sumerall, referring to the recycled material points in rating system. “Grid-wall was used in the first Gold-Level LEED building in Texas. The architect, Betty Trent, was expecting Silver-Level certification, but was awarded gold instead.”

“When researched by people who are looking at the best, most insulated structure they can get, composites rank near the top,” says Dardanis. “They have found our product to be the greenest, most sustainable product out there. It’s driven by an education level of what green building is all about.”