As early as 1969, proponents of ICF touted their insulation, constructability, and light weight.

This year marks 50 years since the first ICF was patented. Werner Gregori, a young German immigrant to Canada, developed the idea while vacationing on the beach. He was a contractor by trade, and between watching kids building sand castles and the foam plastic cooler nearby keeping drinks cold, he had an epiphany.

Within a year, he had developed the first ICF. Called “Foam Form,” each block measured 16 inches high by 48 inches long with a tongue-and-groove interlock, metal ties, and a waffle-grid core. The patent was officially submitted in Canada on March 22, 1966, and the U.S. patent application granted October 24, 1968.

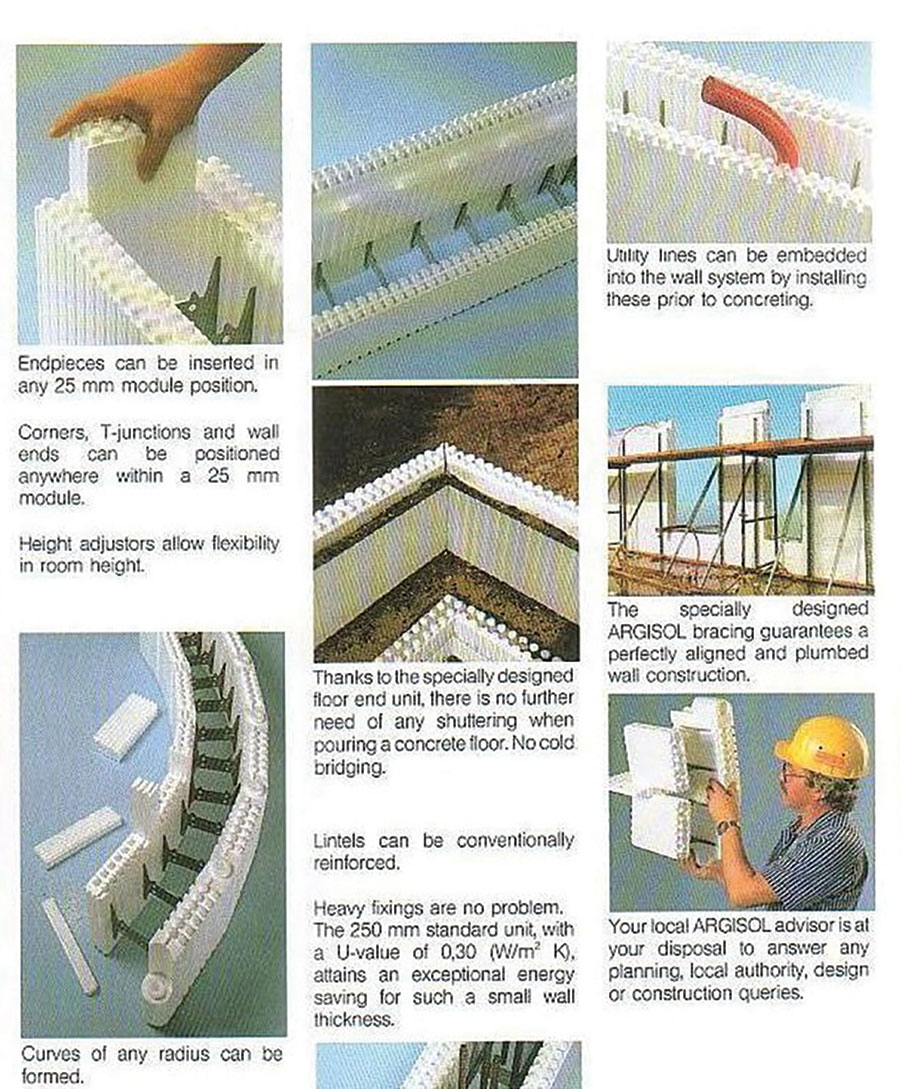

Shortly thereafter, Gregori went to Germany to meet with BASF, the chemical company that invented Styrofoam. His form was not yet patented in Europe, and inventors there developed the idea further. Karl Holik combined EPS bead with portland cement to create the first composite ICF in 1971. A flat wall form was developed by a Swiss company by the name of Argisol.

Taken in late 1969 and early 1970, these pioneering installers likely had little idea how revolutionary ICFs would become.

Meanwhile, the market was expanding in North America. By the mid-1970s, there were 10 or 12 Foam Form licensees doing business in the U.S. and Canada. But then interest began tapering off, and in the early ‘80s, ICFs were facing extinction. Only one distributor—Southwest Foam Forms in New Mexico—was still in business. Rastra shut down manufacturing operations, and Argisol sold off much of its

worldwide rights.

But the idea was too good to die. In 1986, Lance Barrenberg purchased Southwest Foam Forms from the two brothers that started the operation and began looking at ways to improve the product. He redesigned the ties, extending them to outside edges of the foam so they could serve as furring strips. Finishes that previously had to be glued on could now be fastened. He also renamed the company American Polysteel.

The same year that Barrenberg purchased Southwest Foam Form, Pat Boeshart founded Lite-Form Technologies. Rastra moved operations to Arizona and began manufacturing again. Ron Ardres, another ICF pioneer, launched a screen-grid ICF, Reddiform, in 1990.

But it was the flat-wall block that eventually proved dominant. Reportedly, while on vacation in Europe, Mike McIvor saw an Argisol home. He was intrigued enough that he tracked down the North American rights, found a partner, Larry Lichtenegger, and in 1989 started Greenblock. They made virtually no modifications, even keeping the metric dimensions. Seeing an opportunity, a group of investors began ABB BlueMaxx, which offered an Argisol-style ICF sized to imperial measurements.

By 1993, more than 200 homes a year were being built with ICFs, and that was just a hint of what was to come. Sales volumes were doubling every year, and four or five new systems were being introduced annually. (Quad-Lock was founded in 1994, the same year Jay Williamson, a former PolySteel distributor, started 3-10, later Reward Walls). Companies offered blocks in a host of heights and widths, while others made planks and panels as large as 4 feet by 10 feet. Gregori-style post-and-beam blocks competed with flat-wall designs.

With the rapid growth, quality was a concern, as some EPS molders struggled to meet the higher standards required by ICFs, and many builders struggled with code compliance and engineering acceptance. Also, the industry was still invisible to mainstream builders. To address these concerns, the six largest ICF brands banded together to found the Insulating Concrete Form Association (ICFA) in 1995. The Portland Cement Association (PCA) helped the new association get started in the right direction.

By 1997, ICF builders were erecting 8,000 homes a year. Polysteel and BlueMaxx were the leading manufacturers, and the future seemed bright. New ICF brands continued to join the industry (Victor Amend started his ICF company, Amvic, in 1999 and addressed quality concerns by insisting that all molding would be done in-house.)

Most others at the time outsourced molding ICFs, which indirectly led to a major restructuring within the industry at the turn of the century. That year, BlueMaxx settled a long-running lawsuit with Dow over the word “blue” by changing its company and product name to Arxx. At the same time, they planned to build out a nationwide network of distribution centers. To cover the increased overhead, they would have to raise prices significantly. Arxx executives figured the best approach was a personal one, and flew all their top distributors to their headquarters near Toronto to make the announcement. Not surprisingly, the price increase upset many of them, including the five largest distributors in Southern Ontario, who immediately considered starting their own company. Several had heard rumors of a new eight-foot long ICF design developed by one of BlueMaxx’s molders, and they reached out to the molder for details. With days, they had hammered out the basics of a new ICF company to be called Nudura.

This European brochure from the early 1980s demonstrates radius walls, EPS end caps, and turnbuckle bracing.

The other molders that produced ICFs for Arxx weren’t happy about the change either, and five of them developed their own ICF line, called Logix, which hit the market in 2002.

Mike Garrett, formerly a top distributor with Polysteel, launched BuildBlock in 2004. Airlite Plastics, which had been molding ICFs for half a dozen other companies since 1995, announced their own brand of ICF in 2005, to be called Fox Blocks. Summit Publishing launched ICF Builder magazine to cover the industry that same year.

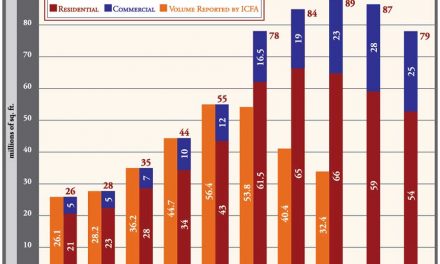

With the building boom of the early 2000s, there was plenty of work to be found. The industry doubled in size between 2000 and 2004, and began gaining market share in heavy commercial construction. (ICFA data shows the industry growing from 7.5 million sq. ft. in ’94 to 56 million sq. ft ten years later.) Driven by a mid-rise boom in the Kitchener/Waterloo area west of Toronto, schools in Kentucky, and religious construction in Arizona, the industry reached historic proportions, with an estimated 80 million sq. ft. of forms installed in 2007.

Then the economic crisis hit. It was a devastating blow, but especially for construction professionals. Many of the smaller ICF brands ceased production, while the larger ones tried to adapt to the new reality. The ICFA trade association, which was already struggling with internal challenges, closed its doors in 2009. Arxx obtained funding from new investors, buying up Eco-Block and Polysteel, but continued to struggle. Fox Blocks, which had the advantage of a diversified parent company, was able to capitalize on conditions and purchase Reward Wall, Formtech, Commercial Block, and in 2010, select assets from Arxx.

As the economy recovers, most insiders admit that consolidation was a painful but much-needed process. Conditions for ICF growth seem brighter than ever before. New ICF associations, one for installers (ICF Builder Group) and another for manufacturers, coordinate industry-wide promotion. The industry has come far from its beginnings in the late 1960s. Now, it stars in TV series and at trade shows. Green building mandates, increased industry cooperation, and a large pool of trained installers all point to a prosperous future for the next 50 years.

Like what you read?

Yearly Subscriptions Starting @ $30