One of the biggest challenges facing the ICF industry—now and for the foreseeable future—is the high cost of transportation.

Simply put, EPS foam is too light to ship long distances cost-effectively. Knockdown forms are a partial solution. Others have assembled a network of molding facilities across North America to reduce shipping distance. At least one tooling manufacturer has taken this solution to the extreme, offering a portable ICF molding facility that could potentially eliminate shipping entirely.

The idea is based, ironically, on the concrete industry, which must confront the opposite problem of moving a product that’s too heavy to move long distances. Ready-mix batch plants dot the U.S. and Canada about every 100 miles, as a 50-mile radius is about the longest distance wet concrete can be hauled effectively.

According to Pat Boeshart, president of Lite-Form Technologies, ICF molders will eventually have a similar distribution. “We have a vision of this industry, when it matures, looking like the concrete industry,” he says. “There will be a series of local foam molding plants, located about 100 miles apart, all over the country.”

According to Pat Boeshart, president of Lite-Form Technologies, ICF molders will eventually have a similar distribution. “We have a vision of this industry, when it matures, looking like the concrete industry,” he says. “There will be a series of local foam molding plants, located about 100 miles apart, all over the country.”

In anticipation of that, EPS mold and tooling manufacturers have begun developing small-scale, highly flexible machines suitable for molding all types of EPS products. Hirsh, Alessio, and Promass all have portable machines under development. But none have taken the idea as far as Lite-Form.

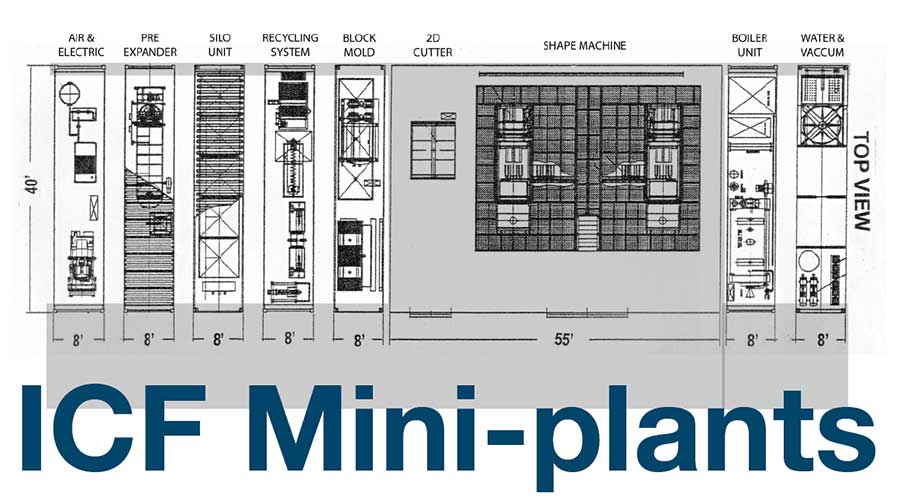

First introduced about three years ago, the company offers containerized “factory kits” that allow ICFs to be manufactured on a surprisingly large scale virtually anywhere in the world.

“What we offer,” says Boeshart “is a complete, mobile polystyrene plant. It’s a complete turn-key molding facility that can literally be set up anywhere there’s fuel and water.”

“It’s very easy to put something like this together,” he continues. The kit consists of ten 40-foot shipping containers filled with equipment and portable 2,000 sq. ft. hoop building.

Three of the containers have machinery that is installed inside the hoop building after it’s been fastened to a concrete foundation. The other crates contain generators, steam plants, and other equipment needed to power the molding operation. The three empty containers could be used as storage space for finished product once the plant is in operation.

Boeshart reports that interest in Lite-Form’s EPS mini-plants is greatest in developing nations where there is no molding capacity. “These people are accustomed to concrete housing, and there’s demand for all sorts of other EPS products as well,” he says. We’re getting multiple leads every week from Ecuador, Africa, and especially the Middle East. They’re building communities with 10,000 homes in them, and at that scale, these mini-plants really start to make sense. You can set up a mobile concrete batch plant right there on site, and pair it with a mobile polystyrene plant, and you’ve eliminated transportation and shipping costs.”

Boeshart reports that interest in Lite-Form’s EPS mini-plants is greatest in developing nations where there is no molding capacity. “These people are accustomed to concrete housing, and there’s demand for all sorts of other EPS products as well,” he says. We’re getting multiple leads every week from Ecuador, Africa, and especially the Middle East. They’re building communities with 10,000 homes in them, and at that scale, these mini-plants really start to make sense. You can set up a mobile concrete batch plant right there on site, and pair it with a mobile polystyrene plant, and you’ve eliminated transportation and shipping costs.”

In the U.S., so far, the reaction has been lukewarm. “Back in 2007, when ICF’s were really rockin’ and rollin’, we were close to closing deals with a few ready-mix plants,” he says, “but right now with the hiatus in the construction industry, the time may not be right. There’s so much extra capacity with existing molders that it doesn’t make sense.” Despite the economy, though, he says he getting a steady number of leads.

Boeshart says that even when the economy picks up, such a facility wouldn’t make ICFs exclusively. “It won’t be economically viable based on just the ICF block,” he says. “It would need to be bundled as deck/tilt/ICF, and possibly shape molding as well.”

Right now, EPS molding facilities are scattered across the U.S. and Southern Canada at about 200-300 mile intervals, and are a mix of shape molders (making refrigerator insulation, bumper parts, shipping padding, etc.) and block molders, (making sheet goods, large rectangular block of foam for cutting, and geofill foam). Shape molders are typically higher-profit, lower volume operations, while block molders focus almost exclusively on volume.

“From our vantage point, we’ve got to get the cost of ICFs down to where they’re affordable to the majority of the population,” says Boeshart. “The material to make them costs $6 and the local retail outlet is pricing them at $20 or $25, and then we wonder why the ICF industry isn’t growing. It’s simple. We’re priced too high.”

Boeshart admits his mini-plants may be ahead of their time. He notes that gypsum drywall was invented in the 1880s, and that laminated OSB I-Joists have been around since the 1940s. Both building technologies took at least 60 years to become well-established. “Someday, these mini-plants may be common,” he says, “but that may not happen for a long time. Right now, we’re staying busy just skimming the cream from the top.”

Hi sire

I’m looking to have an ICF mini-plant here in Dallas Texas.

I have my own patent of the ICF block. My budget is limited in this regard.

would you help me.

Thanks

DR. Nick Manesh

Hi good morning

i am looking to purchase a full ICF Block marking machine including the raw materials and also the molds to manufacture blocks sizes 1220mm length x 305mm height x 102mm / 153mm / 204mm width x 50mm thickness

We are in the process of researching for alternative cost-effective and sustainable building methods for the South African building market. We are very much interested in the ICF Mini Plant. Please supply us with a quotation to set up a production line using your machinery.

Thank you

Dears, I am looking for EPS ICF block molding machine.

Could you please send me more details about your machines?

I would like to disscuss with you technical specification of the machine and possibility to purchase it.

Of course, i mean whole production line (boiler, steam vessels, silo and pre expander for eps beads and moulding machine itself).