By Elise Vue

Photo Credit: iStock

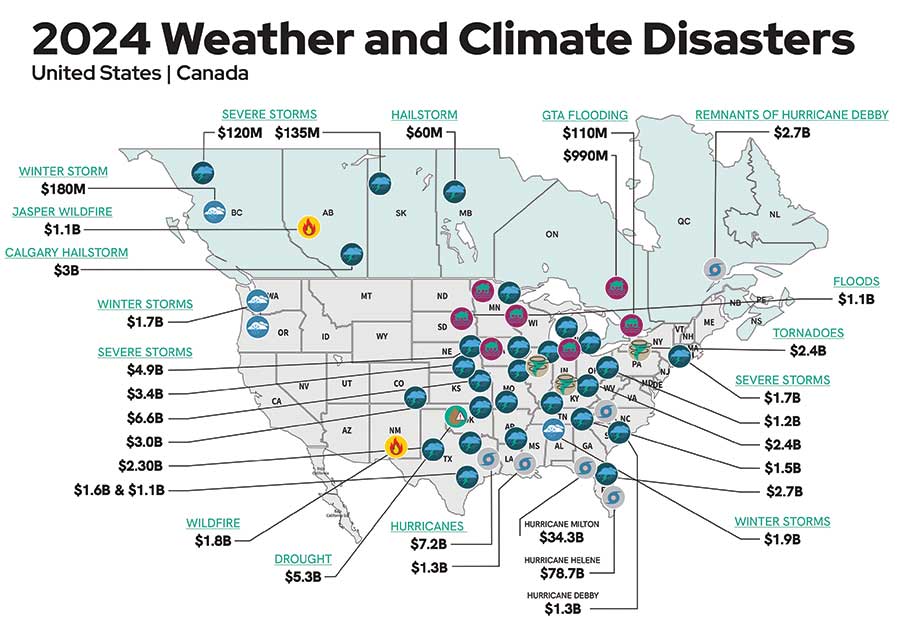

The unprecedented frequency and intensity of natural disasters across the United States and Canada have become impossible to ignore. Hurricanes, tornadoes, flooding, wildfires, and other extreme weather events have resulted in billions of dollars in property damage and devastating fatalities. Yet only 43% of adults in the U.S. feel confident they are prepared for a disaster, according to FEMA.1

With the increasing risk of environmental hazards, this article explores the urgent need for resilient construction practices and highlights actionable hazard mitigation strategies to protect lives and infrastructure, so communities can recover faster in the wake of dangerous weather.

The Cost of Insufficient Building Resilience

Outdated building practices and lack of code compliance are key contributors to the financial and human toll of natural disasters. Structures that are not up to code or have not upgraded to the hazard-resistant criteria of their region are left more exposed to damage and subsequent repairs and reconstruction. The cost to rebuild is also rising due to inflation and supply chain disruptions, making it more difficult for families and businesses alike to bounce back.

A single catastrophic event can cause tens of billions in damage, enough to erase towns and destabilize entire industries. Imagine the short and long-term repercussions to damaged and/or evacuated hospitals, schools, emergency response centers, and sanitation and electrical facilities.

Map showing the financial cost of the largest weather and climate disasters across the United States and Canada in 2024. Source: Nudura

Beyond the direct financial concerns, there are broader implications. The long-lasting effects of unemployment, temporary and permanent health conditions, destroyed agriculture and, of course, loss of lives, cannot be understated. In regions prone to natural disasters, some insurance providers are hiking costs or canceling policies, leaving property owners even more vulnerable.

Disaster Management

Disaster management strategies seek to lessen the impact of natural disasters, including loss of life and property damage. The National Institute of Building Sciences2 (NIBS) and the Canadian Climate Institute3 found that for every dollar invested in adaptation and hazard mitigation, there is $13 in savings in future costs. Building resiliency is just one piece of these comprehensive measures.

There are other harmful impacts of a weather emergency to consider beyond just high winds, rain, and fire, such as:

- Extreme building movement

- Storm surge

- Floodwaters

- Erosion

- Wave forces

- Flood-borne and wind-borne debris

- Fallen trees

- Power outages

These challenges threaten a building’s foundation, mechanical systems (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning), walls, and roofs. So how do we protect all these elements to mitigate damage? Let’s discuss what can be done to create places of refuge within our communities.

Concrete is poured into Nudura ICF walls at this Amherst, Virginia, Habitat for Humanity project. Photo courtesy of Nudura

1. Know your Risk

Emergency preparedness requires knowing the potential hazards in your region. Canada’s Get Prepared website4 has numerous resources to educate residents on what to do before, during, and after an emergency event.

Divided by county, the United States National Risk Index calculates the “potential for negative impacts as a result of a natural hazard”5 based on the expected annual loss, social vulnerability, and community resiliency. These risk levels are conveyed on an interactive map6 to visualize the risk of a particular region for any and all possible disasters.

2. Adapt to Your Region

Before breaking ground on a new structure, building stakeholders should factor all potential environmental stressors of that specific location into its design and construction processes.

Natural disasters threaten the integrity of the entire building, so engineering a structure for a continuous load path7 will more evenly distribute forces and minimize weak points prone to failure. “Failure” in this case could be as minimal as air or water infiltration or as severe as building collapse. In certain areas of high risk, reinforced framing methods, impact-resistant windows and doors, and upgraded exterior wall finishes will help protect the building from debris and moisture ingress.

3. Upgrade to Hazard-Resistant Building Codes

FEMA cites that “one of the most cost-effective ways to safeguard our communities against natural disasters is to adopt and follow hazard-resistant building codes.”8 Dictated by the International Code Council (ICC), building codes are the minimum design and construction standards required for the health and safety of its occupants.

However, a staggering 65% of counties, cities, and towns across the U.S. have yet to adopt modern hazard-resistant building codes as of 20209, leaving these structures even more susceptible to severe and irreparable damage.

Above-code recommendations and hazard-resistant building codes provide enhanced guidelines for more resilient structures to withstand the added stressors of high winds, impact from flying debris, flooding, fire, and seismic activity. Educating decision-makers and advocating for these enhanced codes can help increase implementation across new construction and our existing building stock.

4. Invest in Durable Materials

Prioritizing long-term building safety means choosing the safest, most durable options over the cheapest ones. One proven solution in disaster mitigation is the use of Insulated Concrete Forms (ICFs). With a steel-reinforced monolithic concrete wall that is protected and insulated by two continuous layers of EPS foam, ICF structural walls are impenetrable to virtually any natural disaster.

ICF systems can withstand winds of up to 250 mph (402 km/h) and are impact-resistant, which is particularly helpful in hurricane and tornado-prone areas to shield occupants from flying debris. In the case of fire, ICF walls offer a 4-hour fire rating, giving inhabitants added time to safely evacuate, compared to the 45-minute fire rating of most wood-frame assemblies. This benefit is invaluable for regions susceptible to wildfires.

The Sand Palace along the waterfront of Mexico Beach was still standing after Hurricane Michael in 2018. Photo courtesy of Nudura

If additional durability is specified, fiber-reinforced concrete can be used within Insulated Concrete Forms. In coastal areas, hurricane clips are recommended to strengthen the connection points between roofs and walls and minimize the risk of roofs being torn off during high winds.

5. Build FEMA Safe Rooms and ICC-500 Storm Shelters

In the face of tornadoes, hurricanes, and other forms of extreme weather, the safest place you can be is in a safe room or storm shelter. Designed to meet rigorous standards set by FEMA P-320 and ICC 500 respectively, safe rooms and storm shelters provide occupants with “near-absolute protection”10 from injury or death. These can be standalone structures, such as an above-ground storm shelter, or enclosed within an existing building, like a basement safe room.

While the criteria vary, both FEMA safe rooms and ICC 500 storm shelters can be used in residential and community applications, with some large enough to house thousands of people. Many jurisdictions mandate the incorporation of safe rooms or storm shelters when constructing new public buildings, but widespread adoption takes time. Even if your region does not require them, they should be considered for their hazard mitigation, unmatched safety, and peace of mind.

Home damaged from a tornado. Credit: Shutterstock

Case Study: Surviving Hurricane Michael

Only two Florida counties, Miami-Dade and Broward, are designated as high-velocity hurricane zones (HVHZ) which have more stringent building codes for wind resistance. In 2018, the devastating Category 5 Hurricane Michael hit the city of Mexico Beach, Florida, which falls outside of these counties. The hurricane damaged 94% and completely destroyed 48% of Mexico Beach’s surrounding structures.11 The magnitude of Hurricane Michael’s damage is due in large part to the less strict building codes of this area.

Despite the destruction, one beachfront home remained undisturbed.12 The seemingly hurricane-proof house, named The Sand Palace, was constructed beyond regional codes with Nudura Insulated Concrete Forms and other durable building materials in anticipation of this type of storm. The owners’ proactive approach saved them hundreds of thousands of dollars in renovation and reconstruction costs.

Why Building Resilience Matters

Natural disasters do not have to mean devastation for our communities. Proactive hazard mitigation in the form of building resilience is feasible to save lives, minimize repairs and reconstruction, and speed economic recovery.

By knowing the risks and advocating for regional-specific construction tactics, reinforced building codes, and hazard-resistant materials, the construction and design industries can drive the future where all cities remain strong against extreme weather.

Elise Vue

Elise Vue is the Content Marketing Manager for Tremco CPG Inc., including their brands Nudura, Dryvit, Tremco Sealants, and Tremco Roofing. She leads the research and writing of educational articles for the architecture and construction communities around building science, sealants, waterproofing, exterior finishes, and Insulated Concrete Forms. Her work has been featured in IIBEC Interface, Walls & Ceilings, Construction Specifier, and Pushing the Envelope Canada.

- https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_icpd_2024-national-household-survey-on-disaster-preparedness-findings_05072025.pdf

- https://nibs.org/projects/natural-hazard-mitigation-saves-2019-report

- https://climateinstitute.ca/map-climate-costs-tracker/

- https://www.getprepared.gc.ca/index-en.aspx

- https://hazards.fema.gov/nri/determining-risk

- https://hazards.fema.gov/nri/map

- https://basc.pnnl.gov/resource-guides/continuous-load-path-provided-connections-roof-through-wall-foundation#edit-group-scope

- https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/risk-management/building-science/building-codes-save-study

- https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/risk-management/building-science/building-codes-save-study

- https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/risk-management/building-science/safe-rooms

- https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL142018_Michael.pdf

- https://www.nudura.com/case-studies/mexico-beach-house