End customers are now negotiating directly with the manufacturers and cutting out the distributors.

The times, they are a changin’. We are beginning to see a slight recovery in several facets of the building industry. Homes that are not foreclosures are starting to sell again. Land is being bought on speculation again and commercial developments are starting to provide new opportunities.

However these opportunities have created new challenges the industry has never faced before. Quoting a line from a recent Nationwide Insurance commercial; Years from now, how will we remember this time, as the great recession or the recession that made us great?

There are several models in the market for getting ICFs to the job site. One way is to direct sell to the consumer. Direct selling by manufacturers to end users is nothing new and I am the first to admit that it has some advantages and can work with the right circumstances.

However, the most common model is the manufacturer/distributor relationship. If done right, this can be the most powerful and most successful method. It combines the backing of the larger company with the local knowledge, relationship and support provided by the distributor. In a growing industry like ICFs, support is everything.

Over the last few years, this industry has enjoyed significant positive press. Distributors have been the key to this success. When there is a problem or question, they are right there to make sure the process runs smoothly; not just the sale and installation of the forms, but the before-and-after processes too.

They meet with architects and engineers to get the specs correct and details right. They meet with building officials to ensure proper approvals are made and they are there when the plumber just can’t figure out why his pipes shouldn’t be run in the concrete. I have seen it work successfully time after time.

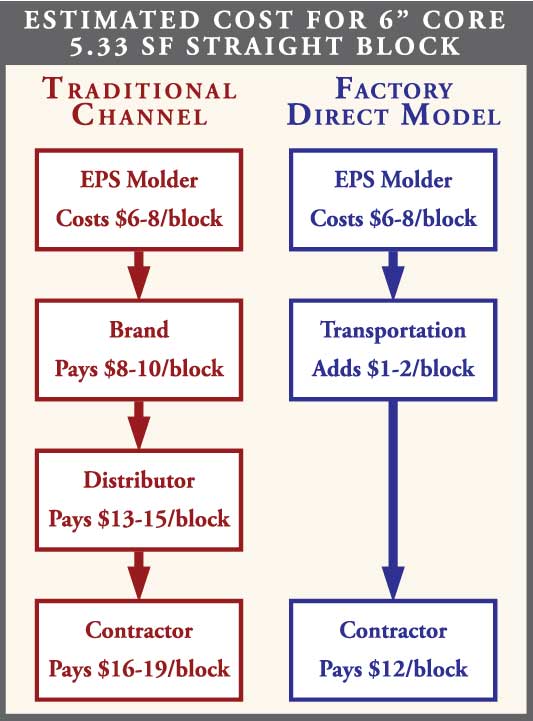

However, this process is unraveling right before our eyes by savvy clients playing the ICF manufacturers like marionette puppets. End customers are now negotiating directly with the manufacturers and cutting out the distributors – all to save a few pennies.

I first saw this happen in the summer of 2006. There was a local builder that was going to build a 30+ production ICF home subdivision. They approached an ICF manufacturer about selling direct. The manufacturer agreed, even though there was an existing, well established local distributor. For the grand opening, the builder really did his job in the marketing department. It was on the headlines, the news cameras were there. Political leaders and dignitaries assembled at the groundbreaking ceremony. Everywhere you looked there were people that were excited about the concept.

Where they succeeded in marketing hype, though, they failed when it came to the actual job. There were three major challenges with the project. The first was it was in a poor location that lacked traffic. Second, it was started at the beginning of the end of the housing boom.

Most importantly, they failed at design. The Santa Fe design, while popular in the Southwest, is not popular inside metro Phoenix. The size was good but the layout was poor. The homes were designed with approximately 1,500 sq. ft. of main level and 1,500 sq. ft. of basement. That might not sound bad. But imagine driving down the street and seeing what appear to be entry-level homes that cost about $300k and an architectural style that will be difficult to resell.

The entire project ended up going back to the bank. After all of the marketing hype, the collapse garnered a lone, simple headline that read “ICF Subdivision Fails”. It is important to note that the headline didn’t mention the manufacturer – only the industry. Proof again that we will succeed or fail not as individuals but as an industry.

Much of this could have been avoided if they had used a team that was familiar with local market conditions. Money was potentially saved on the initial investment, but the failure caused ripple effects throughout the industry. To add insult to injury, the manufacturer was paid only a fraction of what was owed for the material due to the collapse. Had a distributor been involved, product could have been managed and delivered based on payment, or possibly redirected to other paying jobs.

Knowledge of this failure is not just a local issue, but has been discussed nationally by those of us in the ICF industry and production builders alike.

Surprisingly, cost was not the driving force. Instead he cited “industry challenges.” This is just one example of how one failed project has created a cancer that keeps spreading. And the loser is not an individual ICF manufacturer but the industry as a whole.

Another example of this breakdown has been brewing for a couple of years. A local religious organization has committed to build all new churches with ICFs. After a few projects, they decided to go direct to the manufacturers for all their building products in an effort to lower costs. They have gone so far as to not buy local rebar, instead having it imported from China in order to avoid paying sales tax.

The church started out by pitting one ICF distributor against another and in some cases it was rumored that they shared pricing in order to get the other distributor to lower theirs. When they found out this tactic worked, they went directly to the manufacturer and cut out the local distribution channel and applied the same process. In some cases, the savings was literally one or two cents per block.

They saved some money up front, but

what happens when there is a problem in the field? Suppose the order was short a few bundles or corners. Who will supply those when they

are needed immediately? The local distributors are forced to support a client that doesn’t support them.

And what happens if the wall systems are installed incorrectly or if a subcontractor has an issue? Will the manufacturer fly a rep to the jobsite to babysit? Once again, the distributor will be asked to visit the site and take care of the problem. Who pays for his time, effort and overhead? The customer won’t.

To further complicate this issue, members from that organization have told others what has “worked” for them. I now see companies around the country implementing these same negotiating techniques and expecting the

same pricing.

This isn’t a local issue. It’s an issue that if it’s not affecting you now, it will be soon.

I have repeatedly been told by manufacturers that they “can’t afford not to do it”. With the potential long-term ramifications, I have to ask “how can you afford to do it?”

I understand having to be creative just to keep the doors open in this economy. But we need to be extremely careful about losing our integrity along the way.

Projects like those I have mentioned set a precedence. The ICF industry is viewed by many as either over-hyped or easy to pressure into submission. The pressure aspect might not appear to be a huge dilemma now, but what happens in a few years when the economy is better? At what point do we stand our ground? We must manage our clients and not allow them to manage us.

As an industry, we need to come together as a team. This team extends from the manufacturer to the distributor, the design team, construction team and the end user/occupant. This chain must work as one cohesive unit in order to prove what we all know: ICFs are the best building system available on the market today.

Manufacturers need to look beyond streamlining their internal processes at what takes place once that product leaves the plant. How many hands touch it before it becomes a usable structure? Are those hands educated in the proper procedures?

Every member of the supply chain team should be proactive in every project they touch. This exceptional team will be rich with communication and new ideas. Through this team’s uncompromising commitment, the best projects will take shape. Schedules and budgets will be met. Expectations will be exceeded. Excellence will be achieved.

Robert J. Klob is President of Robert Klob Designs, Inc., a full service residential design firm. He can be reached at (480) 968-2474.