By Clark Ricks

In the world of insulated concrete forms, the dozens of competing designs can nearly all be categorized as “block” or “panel” systems. Each has its own advantages and drawbacks.

Since the ICF industry began, most of the leading ICF brands have been preassembled blocks. With this type of ICF, the ties or webs that hold the two foam panels together are permanently molded into the EPS foam at the manufacturing plant. Arxx, Fox Blocks, Reward, and Amvic are examples of this type of ICF.

The other type of ICF, the “knockdown” or panel system, requires the installer to assemble the plastic ties and foam panels at the jobsite prior to or during wall erection. Quad-Lock, ECO-Block, SmartBlock, and IntegraSpec manufacture this type of insulated concrete form. TF System, a vertical ICF, can also be considered a panel system.

Each of these ICF “families” has certain traits in common.

For example, panel systems almost always save on shipping because the foam panels can be packaged much more compactly. Preassembled blocks are said to be faster to stack and stronger during the pour.

But what are the real facts? What do experienced contractors, who have worked with both types of ICF, say about their cost, speed, strength and design flexibility? And what do manufacturers that offer both types of ICF—like Greenblock, American PolySteel and now Logix—say about the relative strengths of each type?

Lastly, before we get too much further into the story, it should be noted that a handful of forms—most notably Nudura, Fold-Form, and Flexx-Block—have a hinged tie that combines the advantages of panel and block systems.

Shipping

“The number one advantage of panel systems is the savings on freight costs,” says Steve Reiter, marketing manager for Greenblock Worldwide.

Because the forms ship flat, with the ties packages separately, a panelized ICF takes up about half the space of a

molded block. Jim Buttrey, sales and marketing manager at IntegraSpec, says the savings works out to be about 42% on a 6” cavity form. “We can fit 5,000 sq. ft. into a 40-foot shipping container and 7,200 on a 53’ transport.”

Colleen Chrencik, who handles shipping and load configuration at Greenblock, reports that with their standard, fixed-web, six-inch cavity block, she can fit about 900 units, or 3,600 sq. ft. on a 53’ van. With the panel system, however, a truck can carry 5,024 sq. ft.

As the core size increases, the potential for shipping cost savings becomes even greater, since knockdown and hinged ICFs are nearly unaffected, while fixed tie designs become considerably bulkier. Increasing the core size from 6” to 8” will usually decrease the number of fixed-tie blocks that will fit on a truck by 30%.

With panel systems, “The only thing that will vary is that there will be slightly fewer ties per box,” says Doug Bennion, director of training and technical services for Quad-Lock, an ICF panel system.

Of course, there are many other factors that affect shipping costs, like the distance between the jobsite and the manufacturing plant. Most fixed-tie ICF brands compensate for higher freight costs by manufacturing the product at more locations. BuildBlock, for instance, has a network of 12 manufacturing plants. Arxx, another fixed tie ICF, has nine.

For smaller jobs, the maximum number of forms you can fit into a container may be a moot point.

So, while it’s safe to say that panel systems do ship more efficiently, whether or not they will actually reduce freight charges depends on the size of the job and its proximity to the ICF manufacturing plant.

Material Handling

But it’s not just long-distance transportation that’s an issue. Often, the ability to efficiently transport the material the last 50 feet to the wall translates to significant gains in productivity.

“It’s not just the shipping, it’s the material handling,” says Buttrey. On one job in southern Ontario, the 53-foot trailer couldn’t turn down the narrow road to the jobsite. “They ferried it the last little bit on trailers pulled by a 4-wheeler,” he says. “The ability to pick up a bundle with 37 sq. ft. of wall and easily move it to where it’s required is huge.”

Jeffrey Childres, formerly a regional sales manager at American PolySteel, has used both the knock-down and fixed tie system the company makes. “If you have to unload a truck by hand, or move stuff around on the jobsite, panel systems are a little faster,” he says.

Stu Oates, an ICF installer who has worked extensively with a dozen leading brands, claims there are efficiency gains for the stacking crew, too. “If it’s a pre-assembled block, the guy will come down off the scaffold and grab a block in each hand,” he explains. “If it’s a panel system, he’ll pick up a bag, which is usually the equivalent of 5 blocks. He’s more than twice as efficient.”

Oates recalls working on an extremely congested job in New York, where the fixed-tie ICFs were “stacked over the entire footprint of the site six feet deep.” Oates said the volume of forms made it difficult to measure and square up the build. “Knockdowns would’ve taken about 1/3 the space.”

Speed

For speed of construction, fixed-tie ICFs generally stack up faster than panel systems, which usually require an extra step to assemble.

“You do have an extra labor step and there are a few guys who don’t want to deal with that,” says Reiter. “It’s a trade off of sorts between the freight and the labor.”

Other factors, like the size of the form, play a major role. Most panel systems are only 12 inches tall, while blocks measure 16 or 24 inches. The extra size of block systems makes big walls go up fast.

“Yes, a block stacks faster,” admits one panel ICF executive, “and that’s fine when you have 250 feet of wall to build with no windows and no turns. But if you have a complicated build, with lots of windows and lots of corners, big blocks are going to eat your lunch.”

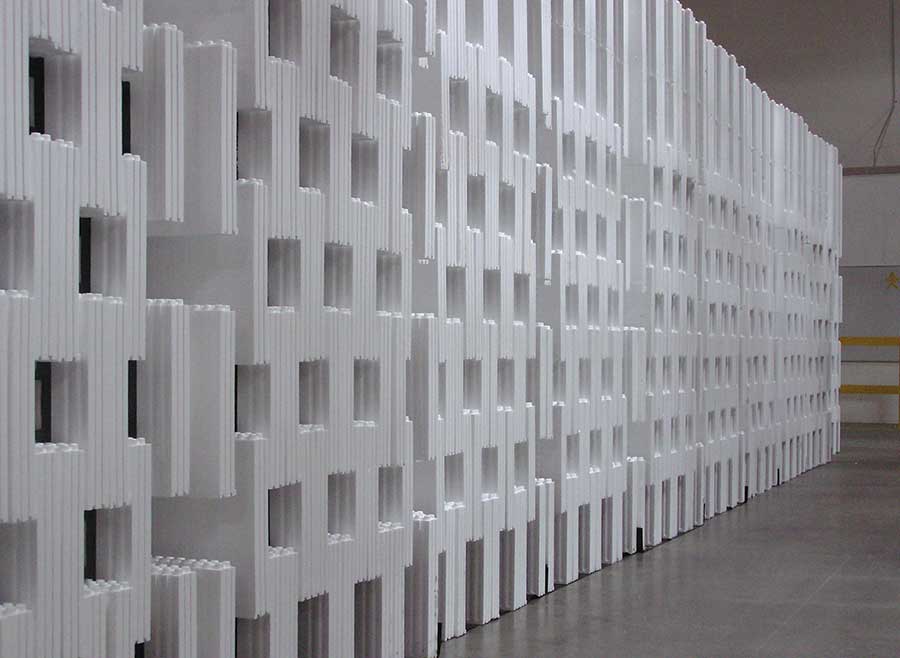

Panel systems have an advantage on complex builds with lots of angles and short wall segments (above). They also are useful on jobs with congested rebar (opposite page) and on jobs where the rebar is erected first.

“In the real word, it would be difficult for a guy with an assembled block to keep up with a guy using a knockdown form,” says Stu Oates.

The difference is in the effort it takes to cut a form. “It’s easier to cut a panel than it is to cut a block,” explains Bennion. “You don’t need to cut the webs, so it’s cleaner and faster.”

As proof, Quad-Lock produced a time-lapse video, available through a link on our website, that shows a basement being built in a day. Mike Hanes, a Michigan-based Quad-Lock builder and his 5-man crew completed the project, including stacking, reinforcing, and bracing, in 9 hours. And it wasn’t a simple box. The 2,800 sq. ft. of walls involved seven 90-degree corners, 6 T intersections, and 7 windows and door openings.

“Any ICF system is going to be much, much easier to cut than masonry,” Childres says. “But unless you have a bandsaw on site that can cut 9” or 13” inch block, you’re going to get straighter, more precise cuts with panels.”

Design Flexibility

If a building design is optimized for ICFs, with wall lengths, ceiling heights, and window openings carefully calculated to match the dimensions of molded block, the structure can be erected incredibly fast.

If it isn’t, panel systems may have an edge. As mentioned above, it’s easier to cut a panel than a block. “The more complicated the build, the bigger the advantage panel systems have,” says Terry Hale, an executive at Insulated Concrete Walls, an ICF installation subcontractor.

Hale has used many of the leading ICF brands on projects across the country, and he says that individual project requirements often determine which type of ICF is used.

A few traits, like exposed furring strips or steel ties, are only available in fixed-web designs.

Also, all of the leading fixed-tie ICF brands offer a large variety of “specialty forms,” such as brickledges, taper-tops,

pilasters, and T-blocks that make otherwise complex projects move forward smoothly.

Radius walls, however, are significantly easier to make with panel systems. “Rather than having to modify a system by removing part of it, it’s usually just a bend,” explains Bennion. “You’re not affecting the structural integrity of the panel. It not only saves time in making the radius, but makes bracing and reinforcing easier as well.”

Rebar Placement

When it comes to rebar placement, panel systems have a distinct advantage. The ability to build one side of the wall at a time, or thread ties through crowded rebar is a capability fixed-tie blocks can’t match.

“In some commercial applications such as parking garages, the amount of steel required is more than the empty ICF can support,” explains George Volker, a territory manager at Logix. “In those cases, the rebar is built up first, and the ICF wall is erected around it. Obviously, panel systems have a real advantage in situations like this.”

Rhyno Stinchfield, former sales director at Quad-Lock, liked to tell of one residential jobsite he visited in Montana, where the vertical rebar for the basement walls had been stubbed at least 10 feet above the footer. When he arrived, the owner was standing on the embankment, playing ring-toss trying to get the ties over the rebar. Bennion says, “Half the time she’s missing, half the time they’re upside down, and everyone is thinking ‘this is going to be difficult.’ Well, Rhyno borrows a guy’s clippers, snips the tie and slides it around the rebar. ‘How’s that?’ he asks.” Needless to say, there was no more ring-toss.

A few panel ICFs, like IntegraSpec or TF System, allow each side of the wall to be built independently. With these forms, the steel can be placed, inspected, and modified independent of wall construction.

Waste

Can one style of block be used more efficiently than another? Not really. It turns out that the biggest issue regarding how efficiently off-cuts are used is tie spacing and whether the interlock is reversible.

“Reversible is infinitely better than a non-reversible block,” says Oates. “On my house, up to the point I got to the gable, I had zero waste. But when I got to the gables, the amount of stuff I had to throw away almost made me cry.”

Childres says, “My experience is that if there are at least two ties in the off-cut, it can be used elsewhere. If there’s just one tie in the piece, it’s scrap.” Panel systems with adjustable tie spacing may hold a slight advantage because with many systems, the tie spacing is variable.

Note also that some panel systems, like Quad-Lock and Smart-Block, form corners using straight-wall components. By eliminating special corner forms (which often have to be ordered in left and right varieties) builders don’t have to order additional materials.

Strength

“There is a perception in the industry that a panel system is not as strong as a block with fixed ties,” says Steve Reiter. “We see our two systems about the same performance-wise.”

This is a hotly-debated topic. It’s hard to generalize, as strength is a combination of many factors, such as foam thickness, strength of tie/foam joint, and spacing between ties. In all of these areas, though, fixed-tie blocks generally score higher than the average knockdown.

“I don’t think there’s any question that an assembled block will give you a stronger block,” claims Gary Brown, director of sales and marketing at Amvic. “Generally speaking, the knockdown forms cannot give you as strong of a form as a factory-assembled block.

Childres argues, “The question of ‘which one is stronger’ is not as important as ‘are they both strong enough to do the job?’ I think the answer is yes.”

He noted that PolySteel’s knockdown Poly-Pro form was put to an extreme test during BRE testing for British code acceptance. “It was an 8” core wall, 12 feet high and 10 feet long. They filled that entire wall segment in less than 20 seconds with 8-inch-slump concrete.” There was reportedly only a single small bulge at the bottom.

Hale, at ICW, says the panel systems he’s used have all performed well in the field. “It comes down to knowing the form and its capabilities,” he says.

The Decision

So while each form type has advantages, it’s impossible to generalize which is the best ICF for the job.

Reiter claims the final decision is mostly personal preference. “Before we publicly introduced our panel system, we sent it to a few distributors to test, and they reported that it performed fine. But interestingly, most of them stayed with the fixed-web block they were already using. It usually comes down to a builder or installer feeling more comfortable with one versus the other.”

Oates agrees. “Here’s the thing,” he says. “whatever people have done first, that’s what they stick with. If someone is used to building with a particular type of ICF, that’s what they like, and they’ll stick with it.”